The Wazzani-incident in the summer of 2002 - a phoney war?

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

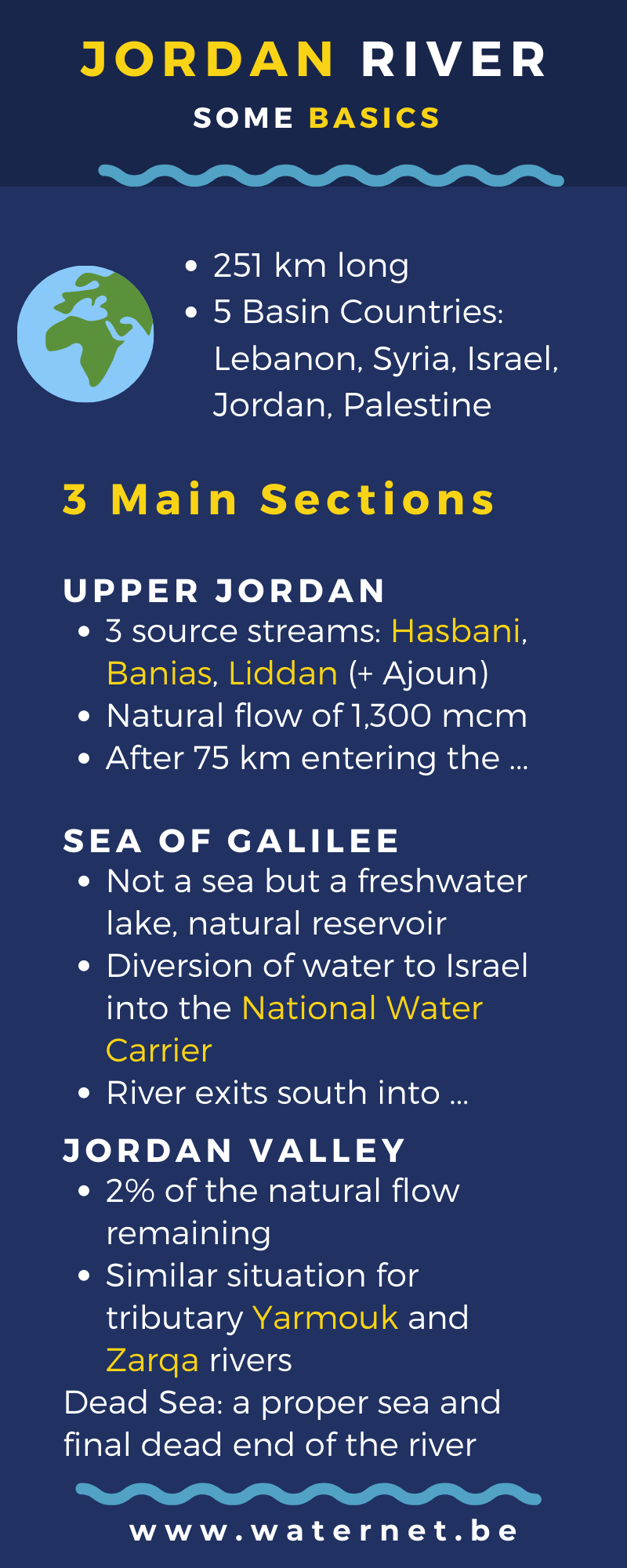

In 2001, Lebanon attempted to construct a pipe on the Wazzani river, in the south of the country and close to the border with the Israeli-occupied Golan. Together with the Hasbani River, the Wazzani contributes 150 million mł of water to the Upper Jordan River, which is a main source of fresh water for Israel. Therefore, Israel was greatly concerned about these Lebanese activities, fearing the future supply of water to its national water system. From 1982 to 2000, this southern part of Lebanon was under Israeli occupation. During a period of 18 years, Israel was in full control of the area, securing its access to one of the main sources of the Jordan River. The Israeli government was repeatedly accused of diverting water from the Litani River basin into the rivers flowing to Israel, through tunnels and pipe lines that cross the water dived between the two systems. After the Israeli withdrawal in the summer of 2000, no evidence was found that could support these accusations. When the Lebanese authorities returned to the area, new plans were laid out to enhance the standard of living in the villages along the Israeli-Lebanese border by supplying them with water.

Water, ideology and security persceptions in Israel

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

Presentation by Stefan Deconinck at the conference on water politics in the Middle East, Middle East Technical University (METU), Ankara, May 2007.

Abstract:

The natural environment of Israel sets its limits on water use for economic development, domestic needs and preservation of nature. Since most of water used in Israel originates from transboundary resources, water policies are not merely limited to management of water resources but interfere with and become part of international politics. Despite multilateral and bilateral peace initiatives, relations between Israel and its neighbours are still based on suspicion and animosity. So are issues related to water resources, which have become one of the core differences between Israel and Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. In Israel, a western-oriented country with a similar package of needs and water uses, water therefore is considered a highly strategic asset. Altering its access to its present water resources, no matter the quantity involved, will be considered a casus belli, as prime minister Ariel Sharon warned the Lebanese government on the Wazzani river issue in the autumn of 2002.

Water policies in Israel have a strong ideological basis. Nearly 60 years after the founding of the country and more than a century after the first migration from Europe, Zionism remains a major justification in decision making in the field of water resources and water management. ‘Making the desert bloom’ still is the creed to for allocating the largest share of water to agriculture, while the economic importance of this sector is minimal. As such, water is essential to the Zionist ideal of making Israel a safe haven for Jews in the world, showing the ability to absorb new immigrants and provide them with a viable and green environment. Touching the water resources directly touches state ideology, and therefore threatens state security.

However, voices are raised in Israeli society, which question the interpretation of Zionism in the 21st century. The outcome of the discussion on Post-Zionism might provide a new appraisal on the essence of water policies as part of the development of the country. In its turn, this might impact the appraisal of water as an asset of external (regional) security.

In this presentation, we will focus on the consequences of ideologically based water policies in Israel, with regard to both internal affairs and external relations. The issue of the current debate on (Post-)Zionism as a change in ideology (can we call it ‘regime change’?) in Israel will be discussed, and its impact on internal and external policies and security will be assessed.

Article: Israeli water policy in a regional context of conflict

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

In 2004, I published an article on the long term Israeli water : "Israeli water policy in a regional context of conflict: prospects for sustainable development for Israelis and Palestinians?"

The article is based on field research and policy analysis, especially the "Long term tasks of the Israeli water sector" document in which a vision was laid out for the development of the sector towards 2020. I am currently working on an update of this article.

Olie op het vuur: water in het Midden-Oosten

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

Interview in De TIjd, 14/07/2001.

Het Midden-Oosten is een ontvlambare regio. Daarvan moet niemand nog worden overtuigd. Dat de regio eveneens een rampzalige droogte tegemoet gaat, is minder bekend. Dat komt omdat water nu eenmaal weinig fotogeniek is, zegt Stefan Deconinck, wetenschappelijk medewerker aan het Centrum voor Duurzame Ontwikkeling van de Gentse Universiteit. Niettemin vormt water een van de hoofdthemas van het Israëlisch-Palestijns conflict. In deze periode van aanhoudende droogte en waterkrapte dreigen de Palestijnen immers opnieuw de dupe te worden. Zolang Israël hun geen gelijke toegang tot water kan waarborgen, is elk vredesakkoord gedoemd om te mislukken.

Een verborgen agenda voor Israël?

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

Interview in De Tijd, 14/07/2001

Door de aanhoudende droogte is de situatie in Israël problematisch geworden. Onder Israëlische hydrologen is een discussie losgebarsten over de mate waarin ze hun watervoorraad onder de heuvels (het bergaquifer) tijdelijk kunnen overexploiteren zonder dat er onherstelbare schade optreedt. Het idee is dat ze nu in de magere jaren met droogte lenen uit de watervoorraad die in de vette jaren met meer neerslag weer kan worden aangevuld, om het in bijbelse termen te verwoorden. Stefan Deconinck heeft zo zijn bedenkingen bij die oplossing.

Water: het stille wapen in het Israëlisch-Palestijnse conflict

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

Opiniestuk in De Tijd, 22/05/2002

Geen enkele oorlog leidt tot vrede. Ook deze niet. Zoveel is duidelijk. De werkelijke uitdagingen waar de partijen in het Midden-Oosten voor staan, liggen veel dieper dan enkel maar de evenementen en conflicten zoals deze zich momenteel aan de oppervlakte voordoen.

Zo is water een fundamenteel mensenrecht. Mondiaal kan het onmiddellijke belang van zuiver drinkwater, sanitair en hyghiëne voor de mens, naast redenen van milieu en duurzaamheid, worden samengevat als de basisremedie tegen ziekte, als economische hefboom en als motor voor sociale ontwikkeling.

Water is politieke pasmunt in de regio

- Written by Stefan Deconinck

Interview in De Morgen, 28/02/2002

'Waterschaarste veroorzaakt conflicten in het Midden-Oosten, maar waterakkoorden bieden ook oplossingen, en dat vergeet men in het strijdgewoel', meent UG-waterexpert Stefan Deconinck.

Welke rol speelt water in het Israëlisch-Palestijns conflict?

Stefan Deconinck: "De bodem van de Westelijke Jordaanoever en de Gazastrook bevat belangrijke watervoorraden, die gedeeld moeten worden door Israël en de Palestijnen. Maar Israël koloniseert veel Palestijnse watervoorraden. Ook de Jordaan is een watervoorraad die in principe kan worden gebruikt door de Palestijnen van de Westelijke Jordaanoever, maar ze is al eerder uitgeput. Uit de cijfers blijkt dat Palestijnen van die gemeenschappelijke watervoorraden per hoofd van de bevolking gemiddeld beduidend minder water kunnen gebruiken dan Israëli's. Een Israëli heeft jaarlijks gemiddeld 320 kubieke m3, een Palestijn 35... Voor Israël moet je dan nog nuanceren: volgens de eigen beleidsdocumenten wordt een onderscheid gemaakt tussen 'niet-joodse en joodse' sectoren. Israëlische Arabieren krijgen voor huishoudelijk gebruik beduidend minder: zo'n 47 m3 ofte bijna drie keer minder dan de joden.

Page 1 of 2